The most common problems in the gallbladder are caused by gallstones which form when there is an imbalance in the concentration of bile salts, cholesterol and phospholipids in the gallbladder. They are common being present in 10-15% of the population. When they cause symptoms the gallbladder should be removed. Gallstones can cause a spectrum of problems that range from not serious such as biliary colic (pain) to conditions that can be serious or even life-threatening such as cholecystitis (inflammation of the gall bladder), jaundice, cholangitis (Infection in the bile ducts) and pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas).

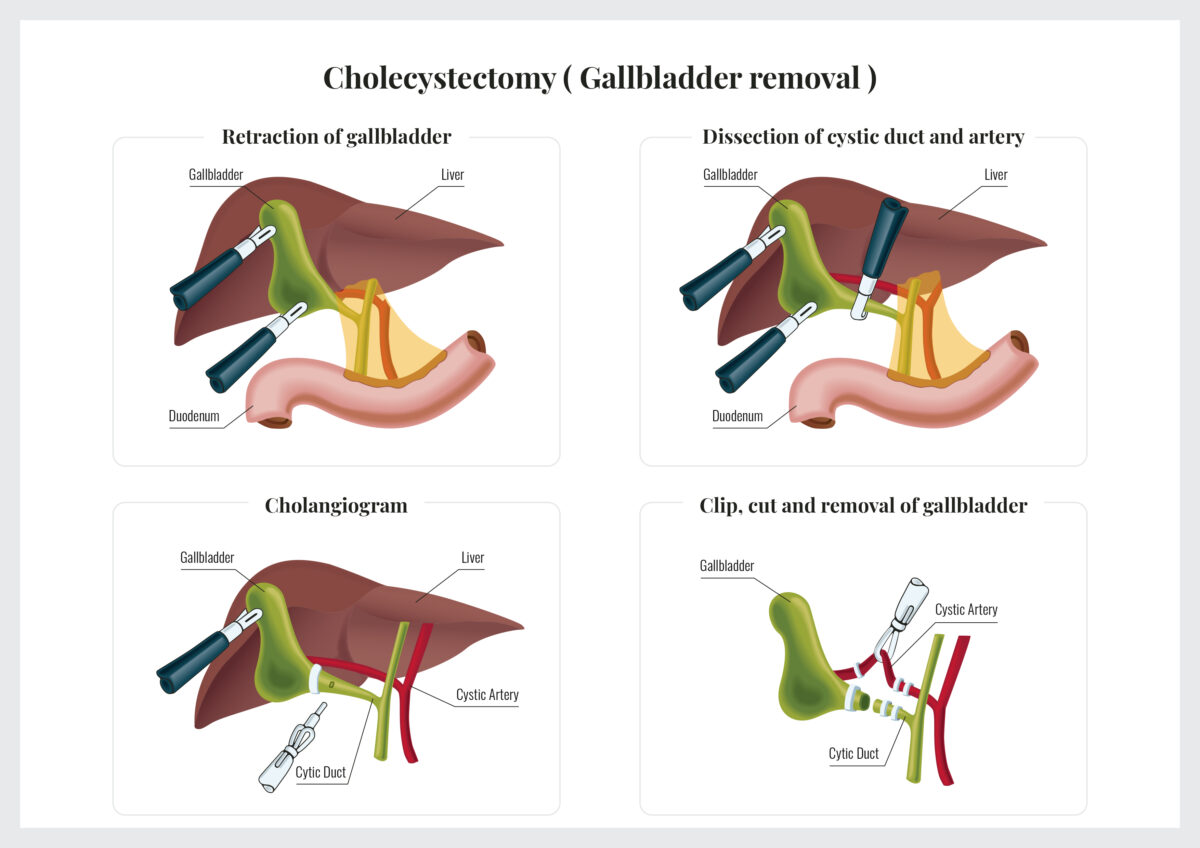

Treatment usually involves surgical removal of the gallbladder. Occasionally an endoscopic procedure is required to remove a gallstone from the bile duct. You should talk to your surgeon about what procedure is appropriate for you.

Cancer of the gallbladder and bile ducts (cholangiocarcinoma) is rare and difficult to treat. Curative treatment requires surgery and often patients have tumours that are not amenable to surgical resection because the tumour is initially silent. Surgical treatment involves the removal bile duct and adjacent organs, which may be the liver or pancreas depending on the position of the tumour. The draining lymph nodes are also removed with the tumour.